Spain will struggle to meet Nato’s defence spending targets due to political divisions and the weak position of the country’s Left-wing government. But another factor complicates this effort: its booming economy.

Pedro Sánchez, Spain’s prime minister, is seeking support from other party leaders to accelerate the country’s progress toward the 2 per cent target, following Ursula von der Leyen’s call for an €800 billion defence spending increase across the EU to counter the threat of Vladimir Putin’s Russia.

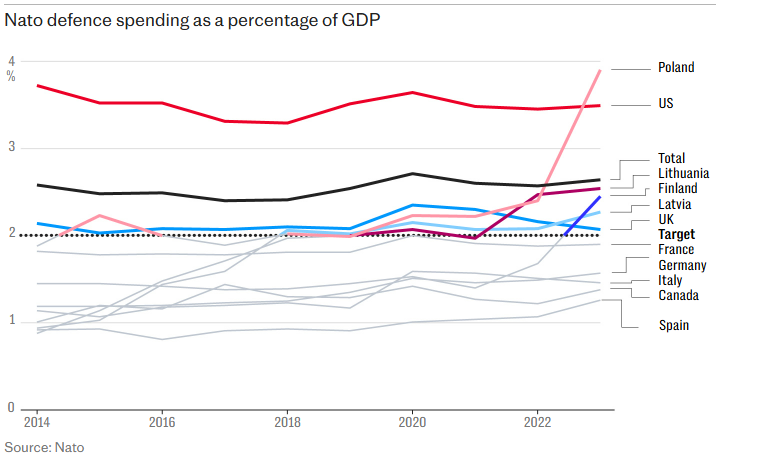

Spain’s economy grew by 3.2 per cent in 2024, making the target even harder to reach. “Countries such as Germany and France are barely registering economic growth, meaning such GDP-based spending objectives are static and not such a moving target.”

However, as Spain’s GDP rises, so does the amount required to meet the Nato benchmark, which is under pressure from the US administration of Donald Trump to increase, possibly to 5 per cent.

Sánchez faces strong resistance within his coalition, with the hard-Left, Catalan, and Basque parties opposing significant defence spending hikes. Government sources suggest the prime minister may bypass parliamentary approval by using contingency funds and cabinet-approved credits for military procurement.

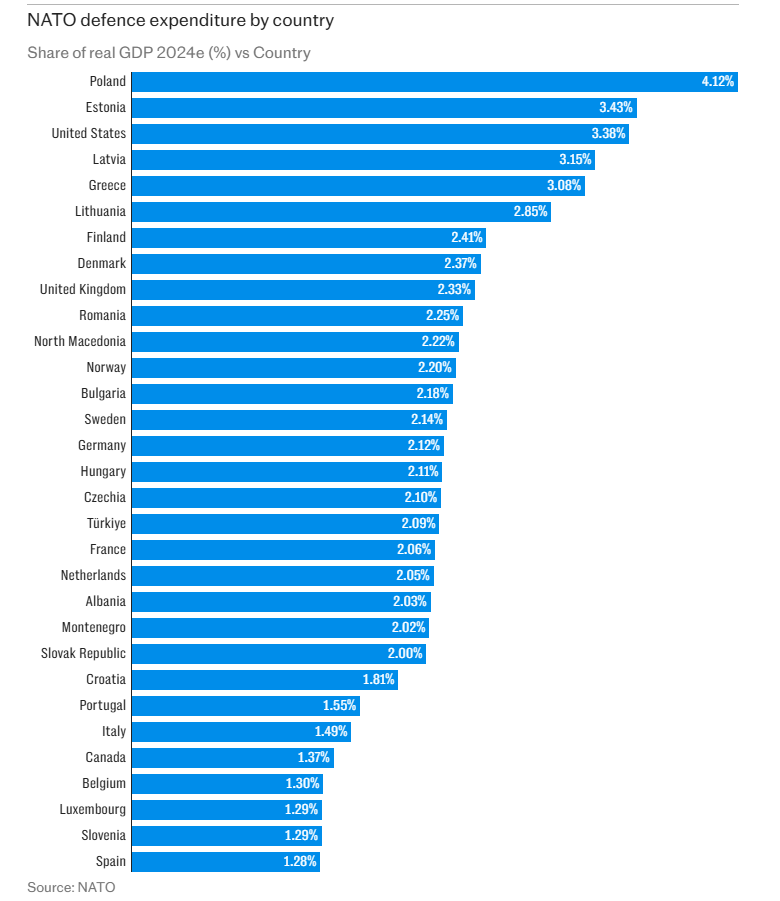

Spain currently spends 1.28 per cent of its GDP on defence, making it “the laggard of all Nato members.” The prospect of increasing this figure has sparked internal disputes within the coalition. Yolanda Díaz, deputy prime minister and leader of the hard-Left Sumar party, recently stated, “We fix nothing by raising the defence budget.”

Díaz secured a commitment from Sánchez that military spending hikes would not come at the expense of social policies. “Mr Sánchez said before Thursday’s meetings with party leaders that Spain would reach the 2 per cent target and he would soon explain to Spaniards ‘how and when.’”

According to El País, achieving the goal would require more than doubling the 2024 defence budget from €17.5 billion to €36.6 billion.

A government source told The Telegraph that reaching the target would be “impossible without political consensus on a reformed national budget,” highlighting Sánchez’s difficulty in passing a new state budget since narrowly retaining power after the 2023 snap election.

“Pedro Sánchez has a problem in explaining to his government the need to raise defence spending,” said Félix Arteaga, a security and defence analyst at Spain’s Real Instituto Elcano think tank. “

He is committed to the target and showing solidarity with his partners in the EU, but his coalition partners are not up for it.” Arteaga also noted that attempts to expand the definition of defence spending—such as including cybersecurity and Guardia Civil budgets—are unlikely to meet strict Nato criteria.

The government could still move forward with funding increases through cabinet-approved credits, as it did with a €1.2 billion military aid package for Ukraine despite resistance from its hard-Left partners. However, Sánchez faces further political challenges.

Spain’s main opposition People’s Party (PP) supports raising defence budgets but remains hostile toward Sánchez. “

Mr Sánchez can expect little in the way of support from PP leader Alberto Núñez Feijóo, with relations between Spain’s two main parties at rock bottom amid a crossfire of accusations of corruption involving politicians from both sides and their family members.”

Feijóo has shown no inclination to collaborate with Sánchez, stating in an interview with El Mundo, “Spain is not a reliable country for Nato nor for the European Union.” He went on to claim that “under Mr Sánchez, Spain has no credibility in foreign or defence policy.”

Santiago Abascal, leader of the far-Right Vox party, was excluded from Thursday’s talks, with the government claiming the party supports Putin.

Why Trump wants to weaken the US dollar — and level global trade